The Cognitive Burden Simulator: A Frequency Self-Report Item

24 dic 2025

UK

,

Spain

This article focuses on using the Cognitive Burden Simulator (CBS) to examine the cognitive load that an average patient may experience when processing the following frequency self-report item:

"Over the past month, how often have you felt anxious or worried about your health? Never / Rarely / Sometimes / Often / Always”

What is Easy About This Item

1. Familiar Language

Words like anxious, worried and health are everyday concepts for most patients. There is no technical jargon or abstract phrasing.

2. Clear timeframe

“Over the past month” is explicit, unlike vague cues such as “recently”. Patients know what window to consider, even if recalling precisely is still difficult.

3. Simple response scale

A 5-point ordinal scale is easy to present and familiar in surveys and questionnaires.

4. Single construct

The question targets one main concept (anxiety/worry about health), not multiple unrelated domains.

What Makes This Item Difficult

1. Recall over 30 days

Episodic memory does not retain every instance of worry. Patients must approximate, leading to estimation, rather than precise recall.

2. Aggregation and frequency judgement

Patients must compress varied experiences into a single summary judgement. This is a demanding cognitive step, especially if the intensity or context of worry fluctuated.

3. Fuzzy response anchors

Words like rarely versus sometimes versus often are subjective. Different patients interpret them differently and this difference is com compounded when you add in further layers, such as age, culture, language and so on. Even the same patient may apply these terms inconsistently over time.

4. Emotional load

Reflecting on anxiety about health can trigger discomfort or avoidance which may distort responses.

5. Attribution problem

Patients may worry about multiple things, such as general life issues, finances, family. Distinguishing health-related anxiety from broader worry adds complexity.

6. Working memory demands

To answer, patients must:

- Hold the timeframe (“past month”)

- Define the construct (“anxious or worried about your health”)

- Recall examples

- Estimate frequency

- And map to a category

- That is 4 to 5 concurrent concepts, already near Cowan’s realistic capacity limit (4±1 chunks).

Summary

This frequency-type self-report item is “easy” in that is uses plain language, a familiar scale and a clear timeframe. But it is “difficult” because it requires recall, aggregation, subjective interpretation of the scale anchors and attribution, all under the influence of possible emotional discomfort.

In practice, patients do not recall every episode of worry; they just approximate. That approximation can be influenced by:

Recency effects, where more weight is placed on the last few days.

Salience effects, especially memorable episodes outweighing mundane ones.

Mood at the time of answering.

CBS Breakdown Table of Item

Level | Component Type | Text | Notes |

Root | Sentence | Over the past month, how often have you felt anxious or worried about your health? | Full item |

1 | Prepositional Phrase | Over the past month | Timeframe definition |

2 | Preposition | Over | Introduces timeframe |

2 | Noun Phrase | The past month | Object of preposition; ~30 days |

1 | Main Clause | How often have you felt anxious or worried about your health | Core question |

2 | Interrogative Phrase | How often | Frequency demand |

2 | Verb Phrase | Have you felt anxious or worried about your health | Predicate |

3 | Auxiliary Verb | Have | Verb support |

3 | Subject | You | Respondent |

3 | Verb | Felt | Main action |

3 | Adjective Phrase | Anxious or worried | Emotional state |

4 | Conjunction | Or | Connects adjectives |

4 | Adjective 1 | Anxious | First emotion descriptor |

4 | Adjective 2 | Worried | Second emotion descriptor |

3 | Prepositional Phrase | About your health | Attribution target |

4 | Preposition | About | Introduces object |

4 | Noun Phrase | Your health | Object of preposition |

1 | Response Options | Never / Rarely / Sometimes / Often / Always | Ordinal scale, subjective anchors |

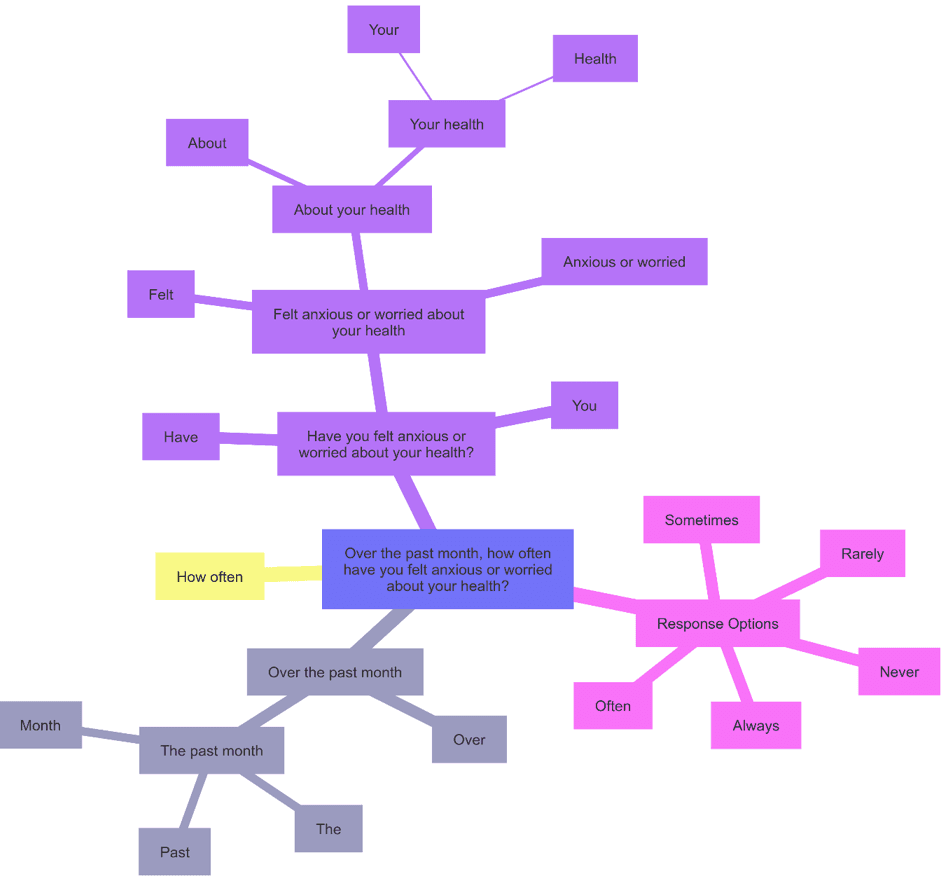

The CBS Visual Map

What This Shows

The easy parts: plain words, such as anxious, worried, health, the clear timeframe (past month) and the familiar 5-point scale.

The difficult parts:

- Recall: scanning 30 days for episodes of anxiety/worry.

- Aggregation: compressing many variable episodes into a single judgement.

- Interpretation: fuzzy scale anchors (rarely versus sometimes).

- Attribution: ensuring worry is specifically health-related, not general.

That means patients juggle at least 4-5 active concepts: timeframe, construct (anxiety/worry), recall of episodes, frequency judgement and mapping to scale. This already matches Cowan’s 4±1 limit under optimal condition and likely exceeds it significantly under stress.

Comparison of COA Item Types

Item Type | Example | Core Task | What’s Easy | What’s Difficult | Working Memory Load |

Binary (Yes/No) | “In the past week, did you experience pain?” | Recall if event occurred; map to Yes/No. | Familiar scale; simple structure; unambiguous response. | Defining what “counts” as pain; remembering episodes over timeframe. | ~4 chunks (timeframe, concept, recall, response). At Cowan’s limit. |

Frequency (Ordinal Scale) | “Over the past month, how often have you felt anxious or worried about your health? (Never / Rarely / Sometimes / Often / Always)” | Recall multiple episodes; estimate overall frequency; map to ordinal anchor. | Plain words; clear timeframe; familiar 5-point scale. | Episodic recall across 30 days; aggregating variable events; fuzzy anchors (rarely vs sometimes); distinguishing health-related worry from other worry. | ~5–6 chunks (timeframe, construct, recall, aggregation, mapping, attribution). Exceeds Cowan’s limit for many patients. |

Global Evaluative | “How would you rate your overall quality of life, considering both physical symptoms and emotional wellbeing?” | Integrate multiple domains; form global judgment; possibly identify contributing factors. | Familiar phrasing (quality of life); structured prompts may help focus. | Abstract concept; weighing domains; attribution of causes; reconciling conflicting experiences; emotional salience. | 6–9 chunks (overall construct, multiple domains, recall, integration, attribution, mapping). Far beyond capacity under stress. |

Key Insights

Binary items feel simple but already press against working memory limits.

Frequency items add the challenge of recall plus aggregation plus fuzzy scales, making them significantly harder.

Global evaluative items pile on abstraction, integration and attribution, often exceeding human working memory capacity altogether.

In short: the more we move from concrete to abstract, from recall to evaluation, the heavier the cognitive burden becomes.

In this next article, we focus on a checklist-style, multi-select patient-reported outcome item. Unlike binary questions or frequency scales, this type of item presents respondents with a list of possible experiences and asks them to indicate all that apply. It is recognition-based rather than recall-based, and it allows for multiple responses rather than forcing a single choice. On the surface it looks simple, just ticking boxes, but cognitively it introduces a different set of demands: scanning through multiple descriptors, holding options in working memory while deciding, managing overlap between terms, and attributing the selected experiences to the relevant health context.

Thank you for reading,

Mark Gibson, Leeds, United Kingdom

Nur Ferrante Morales, Ávila, Spain

September 2025

Originally written in

English