The Cognitive Burden Simulator: Complex Frequency Item on Distressing Mental Imagery

Dec 24, 2025

UK

,

Spain

In the last article, we used the Cognitive Burden Simulator (CBS) to map the cognitive work behind a relatively straightforward self-report item. In this article, we turn to a more complex frequency item:

“Reflecting on your experiences over the course of the past month, how often, if at all, have you found yourself encountering involuntary, distressing mental imagery — such as vivid nightmares or intrusive flashbacks — that appear to be linked, whether consciously recognized or not, to an event that you may perceive as personally distressing or traumatic? Never / Rarely / Sometimes / Often / Always”

Even at first glance, this is quite tough. While the 5-point frequency scale is familiar, the stem is long, densely qualified and emotionally charged. Patients must parse multiple clauses, identify and classify a complex construct and then attribute experiences to trauma, all before they can select an option.

What Makes This Item Easy

Not much, only that it is a familiar scale, and

It involves single selection: only one box to tick, not a checklist of many.

The examples provided, i.e. “nightmares” and “flashbacks” give concrete reference points, at least in the source language, which eases recognition. However, this is heavily culturally bound.

What Makes It Difficult

1. Clause stacking

The stem embeds multiple layers:

Reflecting on experiences

Timeframe of “over the past month”

Involuntary, distressing mental imagery (the core construct)

Parenthetical examples (nightmares, flashbacks)

Attribution to trauma (“linked…whether consciously recognized or not”)

Patients must hold and integrate all of these in working memory.

2. Complex construct definition

Voluntary versus involuntary

Neutral versus distressing

Ordinary dream versus trauma-linked flashback

Sorting experiences into these categories is cognitively heavy.

3. Attribution paradox

The item requires linking imagery to trauma, even “whether consciously recognised or not.”

This places patients in the unusual position of judging unconscious connections.

4. Emotional salience

Trauma, nightmares and flashbacks carry avoidance, stigma and distress.

The emotional burden compounds the cognitive one.

Demands on Working Memory

To answer, patients must juggle:

1. Timeframe (the past month)

2. Instructional frame (reflecting on your experiences)

3. Core constructs (distressing, involuntary mental imagery)

4. Examples (nightmares, flashbacks)

5. Attribution (link to trauma, even unconsciously)

6. Frequency mapping (Never to Always)

7. Qualifiers (“if at all”, “whether consciously recognised or not”)

That is 6 to 7 active concepts at minimum, well beyond Cowan’s 4±1 working memory capacity.

CBS Breakdown Table

Level | Component Type | Text | Notes |

Root | Sentence | Full item | Long, multi-clause |

1 | Instructional Frame | Reflecting on your experiences | Sets metacognitive stance |

1 | Timeframe | Over the course of the past month | Recall anchor (~30 days) |

1 | Main Clause | How often… have you found yourself encountering… | Core frequency demand |

2 | Construct | Involuntary, distressing mental imagery | Core phenomenon |

3 | Examples | Vivid nightmares, intrusive flashbacks | Recognition aids |

2 | Attribution Clause | …linked, whether consciously recognized or not, to an event… traumatic | Causal reasoning + metacognition |

1 | Response Options | Never / Rarely / Sometimes / Often / Always | Familiar ordinal anchors |

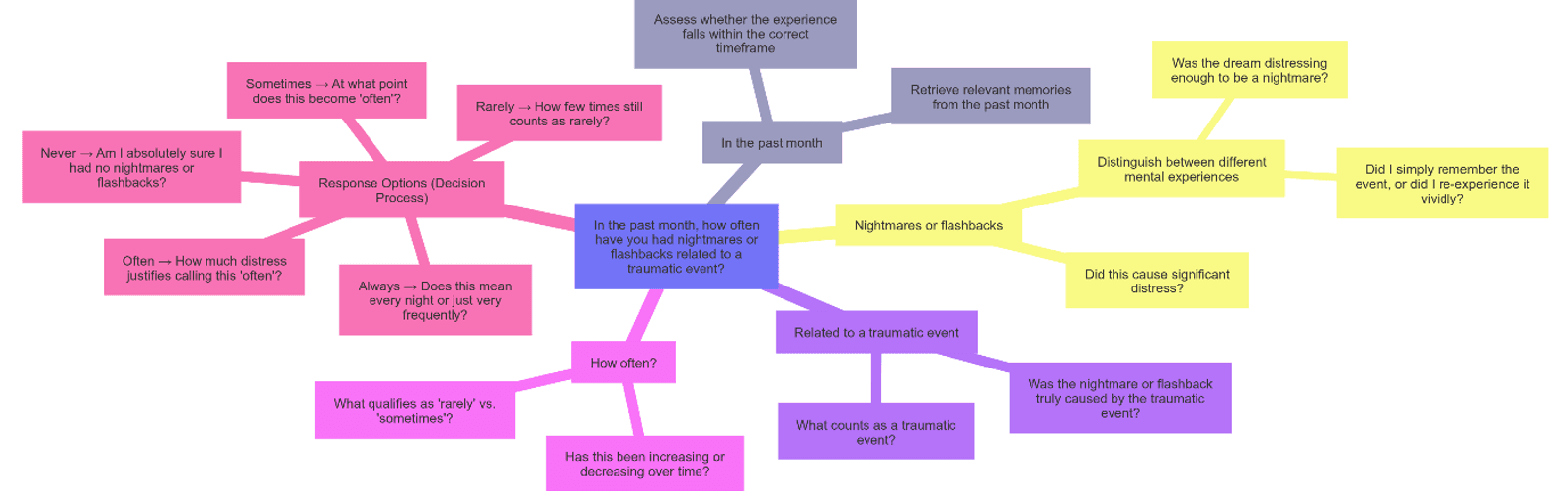

CBS Visual Map (Conceptual Flow)

What We Learn

While this is formally a frequency item, its burden rivals or exceeds that of a global evaluative item. Patients must not simply recall and aggregate but also classify, attribute and emotionally regulate.

In practice, this means:

Parsing four to five subordinate clauses.

Making fine-grained distinctions about involuntariness and trauma linkage.

Managing emotional load from traumatic content.

Holding 6-7 concurrent concepts in working memory.

The CBS shows how question design can turn a seemingly ordinary scale item into a multi-stage cognitive and emotional task. For patients already under stress, this risks responses shaped less by lived experience and more by the structure of the item itself.

CBS Item Type Comparison

Item Type | Example | Core Task | Working Memory Load (chunks) | Why It’s Harder / Easier |

Binary (Yes/No) | “In the past week, did you experience any pain?” | Recall if event occurred → map to Yes/No | ~4–5 | Simple syntax and response scale; but recall, ambiguity of “pain,” and timeframe fuzziness still strain memory. |

Simple Frequency | “Over the past month, how often have you felt anxious or worried about your health?” | Recall multiple episodes → aggregate → map to ordinal anchor | ~5–6 | Familiar 5-point scale and plain words; but 30-day recall, aggregation, fuzzy anchors and attribution increase demand. |

Complex Frequency | “Over the past month, how often, if at all, have you experienced involuntary, distressing mental imagery — nightmares or flashbacks — linked (consciously or not) to trauma?” | Recall → classify (involuntary, distressing) → match to examples → attribute to trauma → map to scale | ~6–7+ | Heavy clause stacking, complex construct definition, paradoxical attribution, and emotional salience all add cognitive and affective burden. |

Global Evaluative | “How would you rate your overall quality of life, considering both physical symptoms and emotional well-being? What factors contribute most?” | Integrate multiple domains → form global judgment → causal attribution | ~6–9 | Abstract construct, integration across domains, attribution of causes, reconciling conflicting experiences, stigma. |

Checklist (Multi-select) | “Over the past month, which emotional effects have you experienced as a result of your health condition? (Select all that apply)” | Recognition → scan list → attribute each option → multi-select | ~6–7 (scales with # of options) | Recognition easier than recall, but scanning multiple descriptors, overlaps, and attribution to health push load upward. |

Key Insights

Binary items look simple but already push patients against Cowan’s 4±1 limit.

Simple frequency items add aggregation and fuzzy ordinal mapping, increasing demand.

Complex frequency items pile on nested clauses, classification, trauma attribution, rivalling global evaluative items.

Global evaluative items require abstraction, integration, prioritisation and attribution, often exceeding working memory limits altogether.

Checklist items rely on recognition rather than recall but the scanning/multi-selection burden scales with the number of options.

In the next article, we shift from frequency and evaluative questions to descriptor-based pain items. These ask patients not only to report whether discomfort occurred but to align their experience with a long list of qualitative descriptors of pain. On the surface, it looks like a straightforward recognition task, but in practice it forces patients to scan, compare and select across multiple overlapping categories while simultaneously weighing dimensions of characteristics, intensity and functional impact. In CBS terms, the hybrid format combines the scanning load of a checklist with the abstraction of a global judgement, pushing working memory far beyond Cowan’s 4±1 comfort zone. We will explore how this kind of item represents one of the heaviest burdens in the COA landscape.

Thank you for reading,

Mark Gibson, Leeds, United Kingdom

Nur Ferrante Morales, Ávila, Spain

September 2025

Originally written in

English