The Nine Circles of Burden: Real-World Constraints on Patient Memory

19 dic 2025

UK

,

Spain

In the last three articles, we traced the story of working memory. We began with Miller’s famous “Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two” (1956) which became more myth than law. Nelson Cowan revised the number downward, showing that most people can juggle only about four chunks of information. Alan Baddeley went further, demonstrating that working memory is not one store but a cluster of fragile subsystems: a phonological loop, a visuo-spatial sketchpad, a central executive and an episodic buffer.

These findings already suggested trouble for Clinical Outcome Assessments (COAs), the questionnaire used in trials and care. Even a simple binary question (“in the past week, did you experience pain? Yes/No”) requires four or five concurrent concepts. More abstract or attributional items (“How would you rate your quality of life, considering both physical and emotional wellbeing?”) stretch to six, seven or more, well beyond Cowan’s limit.

But this is still the laboratory view. Real patients complete COAs in messy conditions: while anxious, fatigued, distracted, cognitively impaired or encountering the instrument for the first time, probably in clinical conditions, possibly while acutely experiencing a symptom. They face dense formatting, ambiguous wording, translations that do not map neatly and digital delivery quirks that hide information off-screen. Many now also outsource memory and even reasoning to digital tools. This is a cultural shift that further reduces effective working memory in practice.

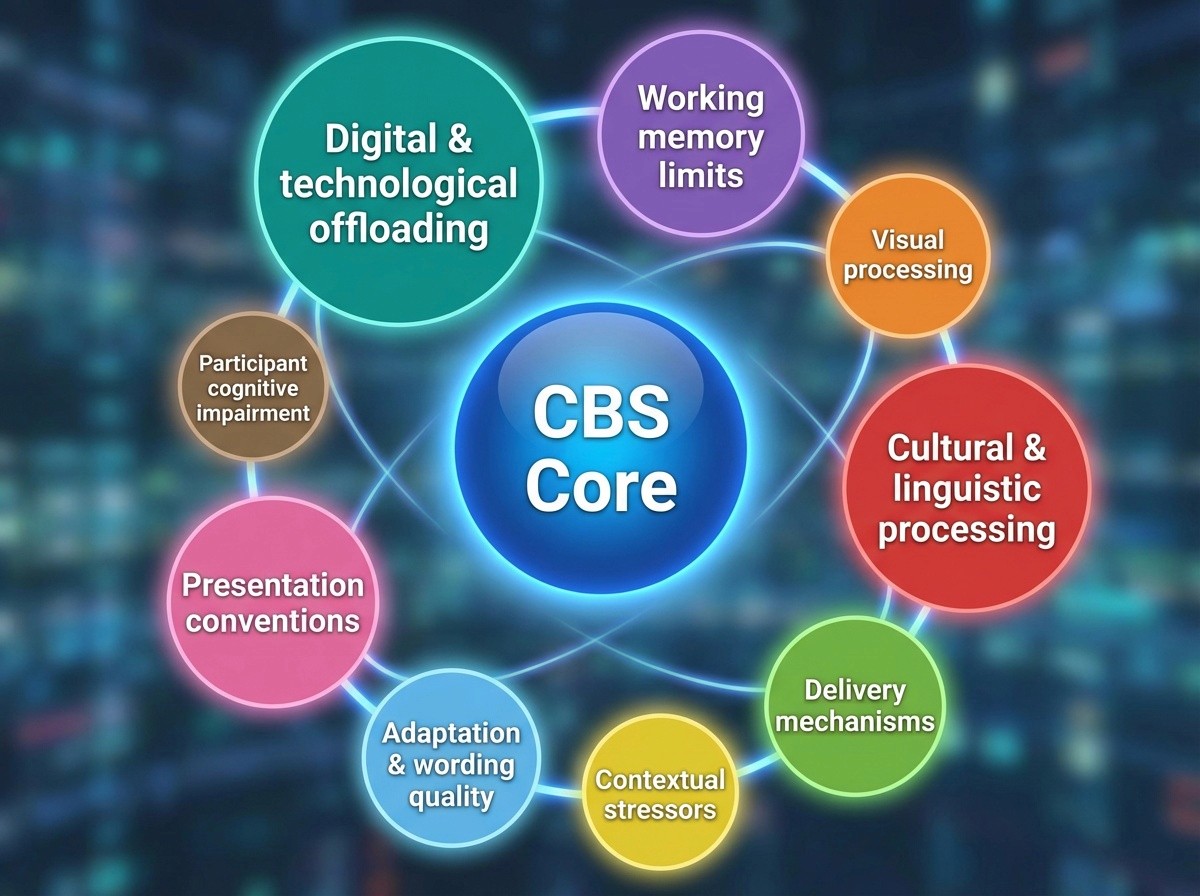

To make sense of this, we developed the Nine Circles of Burden: a layered model that starts with the sterile core, what the Cognitive Burden Simulator draws from, that includes parsing, recall, mapping and expands outwardly through concentric rings of burden. Instead of listing them all again here, we focus on how the circles interact in practice and what they reveal about the hidden demands placed on patients.

The Sterile Core

At the heart of the model is the core, the words and concepts that make up the item. This is what we have built the Cognitive Burden Simulator on. It merges syntactic trees with mindmaps to show how patients parse questions, recall experiences, decide what counts and map answers to a scale. Even the simplest item requires juggling multiple concepts and steps in working memory.

The Cognitive Burden Simulator is based on sterile conditions, but even then, it already illustrates the challenge. Once the outer circles are engaged, the load increases dramatically. This is because the sterile item comes into contact with real-world memory limits, visual and linguistic strain, context, poor adaptation, impairment and digital habits. A binary pain item that might require four chunks in theory can feel like seven or eight when anxiety, bad formatting, small screens or cognitive impairment are added.

This is a crucial insight: the burden is additive. Each circle compounds the others and the interaction matters as much as the individual layer.

How Burdens Multiply

Long stems on small screens

Consider a global item with a long stem: “Over the past four weeks, considering your physical, emotional, and social wellbeing, how would you rate your overall quality of life?” In CBS terms, the patient has to parse the sentence, recall experiences, integrate across domains and produce a rating. This is already demanding.

Now place it on a smartphone screen. The stem scrolls out of view while the scale remains. The patient must hold the entire instruction in memory while deciding. This is an impossible task if they are fatigued or anxious and even harder if they have mild cognitive impairment, which a lot of patients would be completing COAs in clinical settings would have. Here, Circle 1 (memory limits) collides with Circle 4 (delivery mechanisms), Circle 5 (contextual stressors) and often Circle 8 (participant cognitive impairment), multiplying strain.

Checklists and overlap

A checklist of descriptors for pain, such as “aching, stabbing, burning, sharp, dull..” looks simple. You just have to tick what applies. But in practice, the list forces repeated phonological rehearsal, visual scanning and semantic comparison. Overlapping terms create ambiguity. Translations distort further. Patients with reduced attention or executive control (Circle 8) become especially vulnerable to decision fatigue. The burden is not just cumulative across 18 items, it is cross-system, hitting phonological (Circle 3), visual (Circle 2), wording/adaptation (Circle 6) and impairment (Circle 8) all at once.

Formatting habits

Formatting conventions such as ALL CAPS for emphasis or underlining instructions feel natural to designers but add needless strain. In digital contexts, underlining looks like a hyperlink; in left-to-right scripts it clashes with diacritics. All caps reduce legibility. Overloaded scales (seven or more anchors) exceed practical recall precision, especially in translation. These conventions sit in Circle 7 (presentation habits): unnecessary burdens that feel normal because they are institutionalised.

Cultural-linguistic fit

Emotion words, metaphors and idioms rarely carry cleaning across languages. A term like ‘flashback’ may lack an equivalent; ‘loneliness; carries stigma in some cultures. Layout direction (LTR versus RTL versus TBR) changes scanning and alignment.

Here, Circle 3 (cultural/linguistic processing) combines with Circle 2 (visual processing) and Circle 6 (adaptation quality) to produce misreads and missed options.

Digital offloading in the wild

Many respondents habitually rely on search engines and AI tools, remembering where rather than what, and letting systems summarise and synthesise. That habit reduces routine rehearsal and integrative processing. In an unaided COA, such as respondents can feel unusually strained by recall-based tasks, even at short timeframes. That is Circle 9 (digital/ technological offloading) amplifying Circle 1.

What Patients Actually Carry

The CBS allows us to visualise how many “concepts” patients are holding at once.

Binary pain question: around 4-5 chunks in the core of the circle. In real-world use, often 7-8 once formatting (Circle 7), stress (Circle 5), delivery (Circle 4) and impairment (Circle 8) are included.

Global quality-of-life item: 6-9 chunks in the core. With additional circles engaged (visual, cultural, delivery, context, wording, impairment and offloading), it overshoots any plausible human capacity.

What looks like a nice question on the page becomes a cognitive juggling act in practice. Patients are not just recalling; they are navigating formatting, culture, screen design, impairment and institutional habits, all while managing pain or fatigue.

The Nine Circles in Practice (at a glance)

Centre: CBS core (parsing, recall, attribution, mapping).

Circle 1: Working memory limits (Cowan’s 4±1 — in practice often 2–3 under stress).

Circle 2: Visual processing (readability, legibility, layout/alignment).

Circle 3: Cultural & linguistic processing (directionality, vocabulary, stigma, metaphors).

Circle 4: Delivery mechanisms (paper vs eCOA; scrolling stems; hidden anchors; input friction).

Circle 5: Contextual stressors (anxiety, pain, fatigue, time pressure, first-time exposure).

Circle 6: Adaptation & wording quality (ambiguity, overlap, translation gaps, poor eCOA splits).

Circle 7: Presentation conventions (ALL CAPS, underlining, over-bold/italics, overloaded scales).

Circle 8: Participant cognitive impairment (neurologic, psychiatric, treatment-related; reduced WM/attention/executive control).

Circle 9: Digital & technological offloading (Google effect; AI “cognitive debt”; reduced rehearsal and integrative practice).

These circles do not act sequentially; they stack on each other. The practical burden is their sum and interaction at the point of response.

What We Learn

The Nine Circles framework teaches us several things:

Working memory limits are stricter than we think. Forget “seven” or anything near that as the “magic number”; real patients often operate at three or four chunks, fewer under stress or impairment.

Burden accumulates across layers. Visual, cultural, delivery, context, impairment and presentation habits do not operate separately; they multiply.

Digital culture matters. Habitual offloading to device and AI reduces everyday rehearsal and internal synthesis, making recall-based COAs feel unusually taxing.

Design choices matter. Many burdens (jargon, poor adaptation, outdated formatting) are avoidable. Yet they persist because they feel normal to designers and regulators.

COAs measure resilience as much as experience. Patients who “succeed” are not just reporting symptoms but demonstrating the ability to survive the descent through multiple circles of burden.

Implications for Design

Recognising the Nine Circles means rethinking how COAs are constructed.

Design for real capacity (Circle 1)

Assume patients can hold 3-4 concepts at once. Keep items short, simple and sequential. Split global + attribution into steps.

Minimise visual strain (Circle 2)

Clear fonts, adequate size/contrast, uncluttered layouts. Do not use shared=stem grids; present stem and options together (no hidden anchors).

Adapt culturally and linguistically (Circle 3)

Test metaphors, emotion words and directionality with target populations. Do not use idioms. Validate equivalence, not just translation.

Respect delivery format (Circle 4)

Allow time and quiet settings; do not use timers. Take into consideration that paper and electronic are two very different mechanisms of delivery, as are eCOA by phone, by tablet, by laptop, by study-specific hardware.

Write with clarity (Circle 6)

Remove ambiguity and overlap. Replace jargon with plain language. Harmonise scale anchors across items.

Eliminate avoidable habits (Circle 7)

Drop ALL CAPs, underlining and over-bold or italics. Use 4-5 well-distinguished anchors rather than overloaded scales.

Accommodate impairment (Circle 8)

Pilot with cognitively vulnerable groups. Offer simplified modes, larger text, read-aloud options or assisted/caregiver entry where appropriate. Reduce memory dependence, such as showing timeframe badges/ past entries.

Acknowledge digital offloading (Circle 9)

Provide recall scaffolds: calendars, timelines, brief event prompts, examples of “what counts”. Where valid, allow symptom diaries or device logs to support recall rather than punish forgetting.

Conclusion

Dante described nine circles of hell; patients completing COAs often traverse nine circle of burden. At the centre lies the core – the act of parsing and recalling in sterile conditions. Around it radiate concentric rings of memory limits, visual strain, cultural mismatch, delivery quirks, contextual stressors, poor adaptation, entrenched formatting habits, participant cognitive impairment and digital/technological offloading.

The tragedy is that many of these burdens are avoidable. Working memory limits are biological realities, but dense text, bad formatting, ambiguous wording, sloppy adaptation and ill-fitting delivery are design failures. Ignoring impairment and modern digital habits only widens the gap between the instrument and the reality.

The lesson is clarity: COAs should measure lives experience, not working memory resilience. If we can design with the Nine Circles in mind, we can lighten the load, reduce error and capture what matters: the patient’s voice, unburdened.

Thank you for reading,

Mark Gibson, Ávila, Spain

Nur Ferrante Morales, Ávila, Spain

September 2025

Originally written in

English