Mapping Working Memory Biases Across Patient-Facing Documents

9 ene 2026

UK

,

Spain

In the previous article, we examined how working memory biases affect patient-facing documents such as consent forms, package leaflets, instructions for use (IFUs) and digital health tools. We saw that biases like recency, salience don’t just distort Clinical Outcome Assessments (COAs) but also shape how patients read, recall and act on health information (or any information) in other contexts.

In this article, we take the next step. Rather than looking at each document type in isolation, we map the full set of working memory biases across all the major categories of patient-facing material. This comparative view allows us to see which biases are most likely to appear in each setting, what distortions they produce and how they overlap. By laying them out side-by-side, we can begin to see patterns that explain why certain formats fail and what can be done to make them more usable.

Recency and Primacy

Two of the most basic biases in working memory are recency and primacy: the tendency to recall what comes at the end and what comes at the beginning, while neglecting what lies in the middle.

In consent forms, patients often remember the first-listed and the last-listed risks, leaving the bulk of the content in the middle forgotten. This explains why clinicians sometimes find that patients recall only the introductory explanation and the final signature clause, but little else. Information leaflets show the same pattern: side effects at the top and bottom of the list are more likely to be remembered, while those buried in the middle vanish. IFUs suffer when patients remember the first step and the last step but skip essential middle instructions, such as priming a device or disposing of waste. And with apps and wearables, the most recent alert almost always dominates, even if earlier ones were more clinically important.

Salience and Anchoring

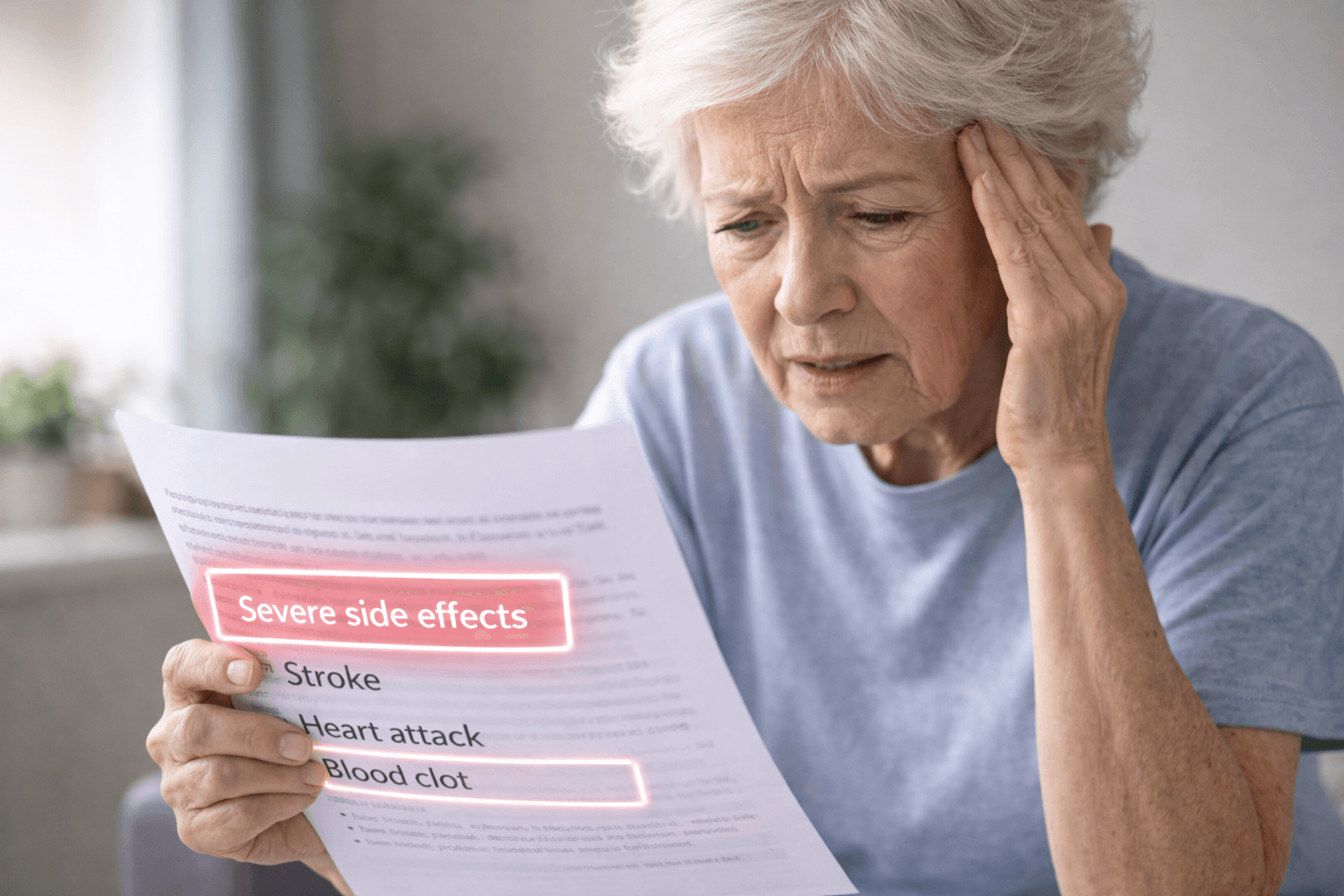

Working memory is not democratic; it privileges what is vivid or emotionally intense. Salience bias ensures that rare but dramatic events outweigh common but mundane ones. Anchoring bias adds a further distortion: once an extreme event is remembered, it becomes the reference point against which all other judgements are made.

In consent forms, this means that catastrophic but rare risks like “death” or “paralysis” anchor patients’ sense of danger, overshadowing far more common risks such as nausea or fatigue. Information sheets suffer similarly, with patients remembering hair loss or seizures while disregarding routine side effects. In IFUs, one bad experience with a device, for example, an accidental needle stick, can anchor perception of risk and dominate future use. Apps and wearables are particularly prone to anchoring: one alarming alert such as “irregular heartbeat detected” can define the user’s sense of their health for weeks, even if subsequent readings are normal.

Mood-Congruent Recall and Current State Bias

Working memory is influenced by the patient’s emotional state at the moment of recall. Mood-congruent recall means that means that negative moods bring negative experiences to mind more easily, while positive moods bring positive ones. Current state bias extends this effect: the patient’s physical and emotional condition at the time of engaging with a document colours their interpretation.

For consent forms, this means that anxious patients focus on risk and ignore benefits or safeguards. For information sheets, someone who is already feeling unwell is more likely to recall severe side effects and disregard benign ones. In IFUs, stress during device use shrinks capacity and makes instructions harder to follow, amplifying the memory of warnings. For apps, mood colours interpretation of alerts: a neutral “activity low” reminder may be read as threatening when the user is already worried.

Averaging, Neglect of Variability and Simplification

When asked to summarise experiences or information, people rarely keep the full detail. Instead, they compress data into simple averages or broad categories. This leads to averaging bias, neglect of variability and simplification.

In consent forms, patients may compress dozens of risks into a vague sense of “high risk”, losing the ability to distinguish between probabilities. In information sheets, patients collapse fluctuating side effects into a single stable judgement such as “sometimes”, masking cyclical conditions. IFUs are often simplified into broad steps like “set up the device”, while essential sub-steps are lost. And apps encourage simplification by presenting complex metrics as binary judgements: healthy versus unhealthy, good sleep versus poor sleep.

Interference and Overlap

Working memory also struggles when multiple similar items compete for attention. Interference occurs when similar concepts blur together; overlap creates confusion about boundaries.

Consent forms are prone to this because legal right are often expressed in overlapping terms, such as “withdrawal rights” versus “data protection rights”. Patients may not understand the distinction and may forget one or both. Information sheets often list side effects that overlap semantically, such as fatigue, tiredness, lethargy, which makes it unclear whether they are different or the same. IFUS frequently contain multiple warnings that sound alike, such as “do not shake” and “do not drop”, which leads to patients to treat both as redundant. Apps and wearables contribute their own interference, with similar icons or notifications for different functions confusing users.

Telescoping and Omission

Telescoping is the misplacement of events in time: remembering something as more recent than it was (forward telescoping) or as more distant (backward telescoping). Omission arises when working memory simply drops information because there is no room to hold it.

For consent forms, this can mean misremembering when certain risks were explained. Patients may believe they were told later than they were. For information sheets, it can man misplacing symptoms in the wrong recall window, which distorts perceptions of drug safety. IFUs are highly vulnerable to omission: small but essential steps like hand washing or priming are dropping under capacity strain. Apps show omission in the form of alert fatigue: frequent low-level alerts are ignored, even if clinically relevant.

Satisficing and Response Order Effects

When tasks are too demanding, people take shortcuts. This is satisficing: doing just enough to get by rather than answering carefully. Response order effects add another distortion: choosing earlier options simply because they appear first.

In consent forms, satisficing appears as patients skimming and signing without full comprehension. In information sheets, it shows up as patients attending only to the first few listed side effects. In IFUs, it leads to skipping warning and moving straight to the action. And in apps, satisficing takes the form of swiping away alerts without considering them or acting only on the first notification in a batch.

Social Desirability and Confirmation Bias

Finally, memory interacts with motivation and self-concept. Social desirability bias leads patients to downplay experiences that are stigmatised or embarrassing. Confirmation bias makes them recall information that supports their existing beliefs.

Consent forms are shaped by these dynamics when patients minimise their fears to appear cooperative. COAs suffer when patients underreport sensitive side effects such as sexual dysfunction. IFUs can be distorted when patients conceal misuse or errors out of embarrassment. Apps and wearables are subject to confirmation bias: alerts are interpreted in ways that confirm what the user already believes about their health, whether optimistic or pessimistic.

A Comparative View

To make these patterns clearer, it is helpful to look across document types side by side. The table below summarises how each bias manifests in consent forms, information sheets, IFUs and technologies like apps/wearables.

Bias | Consent Forms | Information Sheets | IFUs | Apps/Wearables |

Recency | Last clauses remembered | Recent side effects dominate | Last steps remembered | Latest alerts prioritised |

Primacy | First risks recalled | First items recalled | First steps recalled | First alerts weighted |

Salience | Dramatic risks dominate | Striking side effects dominate | Unusual warnings dominate | Loud alerts dominate |

Mood/State | Anxiety amplifies risks | Anxiety amplifies negatives | Stress amplifies warnings | Mood colours alerts |

Averaging/Simplification | Risks blurred together | Side effects compressed | Steps compressed | Data reduced to simple categories |

Interference | Legal rights blur | Overlapping side effects | Multiple warnings interfere | Similar icons interfere |

Anchoring | Catastrophic risk anchors | Rare side effect anchors | One past error anchors | Alarm anchors |

Telescoping | Misplace risks in time | Misplace symptoms | Misplace errors | Misplace alerts |

Omission | Routine clauses forgotten | Common effects omitted | Small steps omitted | Frequent alerts ignored |

Satisficing | Skim and sign | Skim lists | Skip warnings | Swipe alerts |

Response order | Early risks recalled | Early items recalled | Steps followed in order read | First alert acted on |

Social desirability | Downplay concerns | Underreport sensitive issues | Hide misuse | Ignore alerts |

Confirmation | Interpret to confirm beliefs | Recall side effects consistent with expectations | Focus on errors confirming difficulties | Interpret alerts as confirming decline |

Conclusion

When we look at patient-facing documents through the lens of working memory biases, a pattern emerges. Each format is vulnerable in different ways but the underlying mechanisms are the same. Consent forms collapse under order effects and salience. Information sheets overwhelm through volume, overlap and anchoring. IFUs falter under omission, interference and stress. Apps and wearables mislead through recency, salience and confirmation bias.

The matrix highlights that these distortions are not isolated problems but systemic. Every patient-facing document assumes a level of memory capacity and neutrality that simply does not exist. If we want these materials to be truly effective, they must be designed with memory’s biases in mind: chunked information, repeated key points simplified layouts, randomised lists and opportunities for retrieval rather than recall.

Bias is not a flaw of patients but a feature of human cognition. Recognising and adapting to these limits is essential for ethical, effective communication in healthcare. It should not be an option.

Thank you for reading,

Mark Gibson, London, United Kingdom

Nur Ferrante Morales, Ávila, Spain

September 2025

Originally written in

English