The Cognitive Burden Simulator: Visualising the Hidden Cognitive Burden of Clinical Outcome Assessments

Dec 18, 2025

UK

,

Spain

When patients encounter Clinical Outcome Assessment (COA) items, whether in clinical trials, routine care or self-report questionnaires, they engage in a complex set of mental processes that often go unseen. These processes involve not just reading words but also interpreting structures, recalling experiences, making judgements and aligning responses with predefined scales. Each of these steps adds to what can be thought of as the cognitive burden of completing a COA.

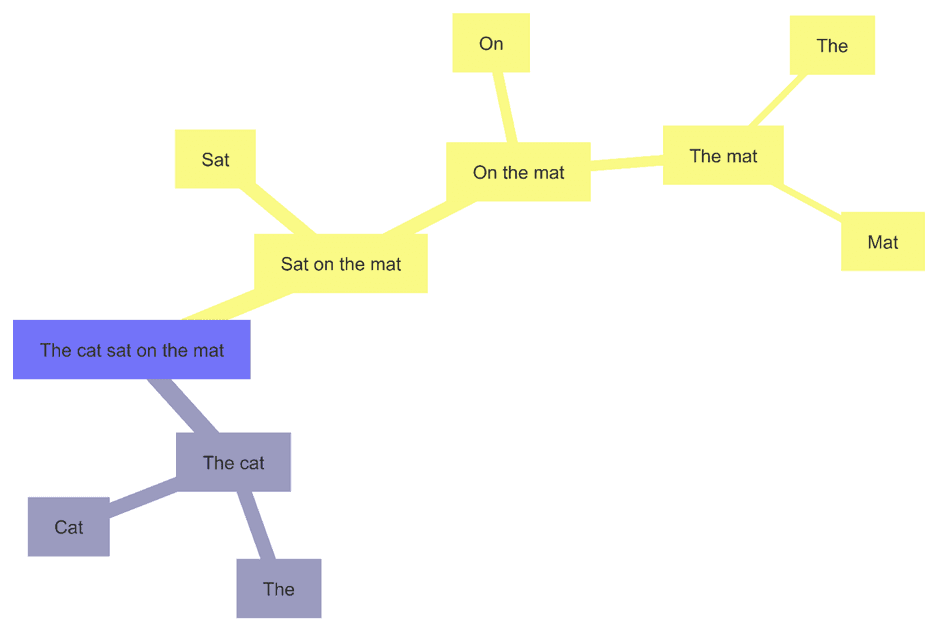

In this series of articles, we use AI-generated simulations to illustrate how patients might process different types of COA items and other patient-facing documents, such as a Patient Information Leaflet. These are not from empirical studies but rather conceptual models designed to shine light on the mental work involved in seemingly very simple tasks. To do this, we merged Chomskyan syntactic tree diagrams, which map the grammatical structure of sentences, with mindmap-style visualisations that capture branching cognitive processes. We generate these diagrams using Mermaid Chart, creating a hybrid way of representing how reading unfolds in the mind.

We called this hybrid diagram the Cognitive Burden Simulator (CBS). This is our illustrative model for showing how patients may process clinical outcome assessment (COA) items and other patient-facing documents.

The CBS does not represent an exact cognitive process in the brain. Rather, it functions as a didactic framework that makes visible the likely layers of parsing, memory load, decision-making, and visual scanning involved when a person reads and responds to an item. By starting with simple sentences and moving to increasingly complex COA examples, the CBS helps illustrate how cognitive burden expands as items become more linguistically and structurally demanding.

The journey begins with something familiar and straightforward: a simple English phrase: “The cat sat on the mat”. This baseline example demonstrates how syntactic parsing and mental mapping look for a native reader. From there, we gradually increase complexity by layering in COA-style questions, from basic frequency items to shared-stem structures, multi-select or ranking tasks and, finally, translated items that introduce additional challenges for non-native speakers.

Example 1: The Cat Sat on the Mat

This is how the simple sentence, “the cat sat on the mat”, may be processed:

The following table illustrates a stylised model of syntactic parsing, based on linguistic theory. It represents one way of conceptualising the likely cognitive steps a native English speaker takes when reading this sentence.

Level | Component Type | Text | Notes |

Root | Sentence | The cat sat on the mat | Whole sentence |

1 | Subject | The cat | Noun Phrase |

2 | Determiner | The | Defines the noun |

2 | Noun | Cat | Head of the subject NP |

1 | Predicate | Sat on the mat | Verb Phrase |

2 | Verb | Sat | Main action |

2 | Prepositional Phrase | On the mat | Provides location |

3 | Preposition | On | Introduces PP |

3 | Noun Phrase | The mat | Object of preposition |

4 | Determiner | The | Defines the noun |

4 | Noun | Mat | Head of the NP |

Below is the mindmap representation of how the sentence is likely to be processed:

Diagram created by Mermaid Chart.

Interpreting the Diagram

When we say, “this is how this sentence is processed”, we are not claiming that every person actually parses the sentence in exactly this way in real time. Instead, what we are doing is:

Using linguistic theory à la Chomsky to model how the sentence can be decomposed structurally.

Mapping that onto a mindmap representation to simulate possible cognitive steps a reader might go through.

Presenting this as an illustrative framework only and not as a literal reflection of neurocognitive processes in the brain.

‘Steelmanning’ the Model

We find it hard to believe we have just used that YouTube podcaster verb ‘to steelman’. The manosphere will be proud, we guess. What we really mean is we are trying to self-critique our approach to how we are trying to illustrate the cognitive burden when processing and the unlikely pairing, if not merging, of Chomskyan syntactic trees with mind-mapping. So, let us critique:

From a linguistics perspective:

This is a faithful representation of constituent structure parsing in generative grammar.

Readers of English would normally parse “the cat” as a subject noun phrase and “sat on the mat” as a predicate verb phrase.

This is uncontroversial in formal syntax.

From a psycholinguistics perspective:

Human readers often parse incrementally in a way that mirrors the syntactic tree structures, such as first recognising “the cat” as a noun phrase.

Eye-tracking studies support the idea that readers build syntactic structures in chunks.

However, the mindmap/tree is a stylisation, not an exact cognitive replace.

What Would an Exact Cognitive Replica look like?

If we wanted to move beyond stylised trees, an exact cognitive replica would need to reflect how the brain actually processes language in real time. That involves a much richer set of dynamics:

1. Neurocognitive dynamics

Different brain regions activate at different points, such as Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas, angular gyrus and prefontal cortex.

Processing happens on the order of milliseconds, although measurable, particularly where semantic mismatch occurs and syntactic reanalysis.

Parsing is not linear but probabilistic and parallel, with multiple possible interpretations briefly held before one is selected.

2. Psycholinguistic process

Incremental parsing: words are interpreted as they come in, not after the sentence ends.

Prediction: readers anticipate upcoming words (after “the cat”, the brain predicts a verb)

Working memory load: incomplete structures are stored while waiting for resolution.

Eye-tracking evidence: fixation, regression and saccade patterns show how readers adjust moment by moment.

3. Individual and contextual variation

Native versus non-native speakers engage different processing strategies.

Different scripts (alphabetic, logographic, syllabic) impose different visual and cognitive demands.

Why We Used Stylised Trees

Blending Mindmaps and syntactic trees give a clear didactic snapshot of one plausible path of parsing. They deliberately:

Simplify by showing a single neat structure rather than messy alternatives.

Ignore noise such as misparsing, regressions or individual variability.

Resemble formal syntax more than actual neural dynamics.

This makes them useful for illustrating the principle of cognitive burden, even though they are not true replicas of what happens in the brain.

An exact cognitive replica would look very different: less like a tidy branching tree and more like a dynamic simulation that combines probabilistic parsing models, eye-tracking heatmaps, ERP brainwave timelines and working memory fluctuations. That would be closer to reality but also far less transparent for teach and communication.

From a Clinical Outcome Assessment (COA) perspective:

The value of this model is illustrative: showing how even a very simple sentence involves multiple layers of parsing.

This sets the stage for showing how COA items, which are typically longer, more complex and more content-dependent, may impose exponentially greater cognitive burden.

Thank you for reading,

Mark Gibson, Leeds, United Kingdom

Nur Ferrante Morales, Ávila, Spain

August 2025

Originally written in

English