Beyond the Basics: Additional Biases That Distort COA Responses

Jan 9, 2026

UK

,

Spain

In a previous article, we explored the core working memory biases that shape how patients answer Clinical Outcome Assessment (COA) items: recency bias, salience, mood-congruent recall, averaging, interference, anchoring to extremes and omission. Together these showed that COA responses are not neutral reflections of lived experience but are filtered through the limits and quirks of human memory.

But those are only the starting point. Cognitive psychology highlights a wider set of secondary biases that come into play when tasks are long, repetitive or emotionally demanding, exactly the conditions in which patients complete COAs. These additional biases interact with working memory limits and add further noise to patient-reported data.

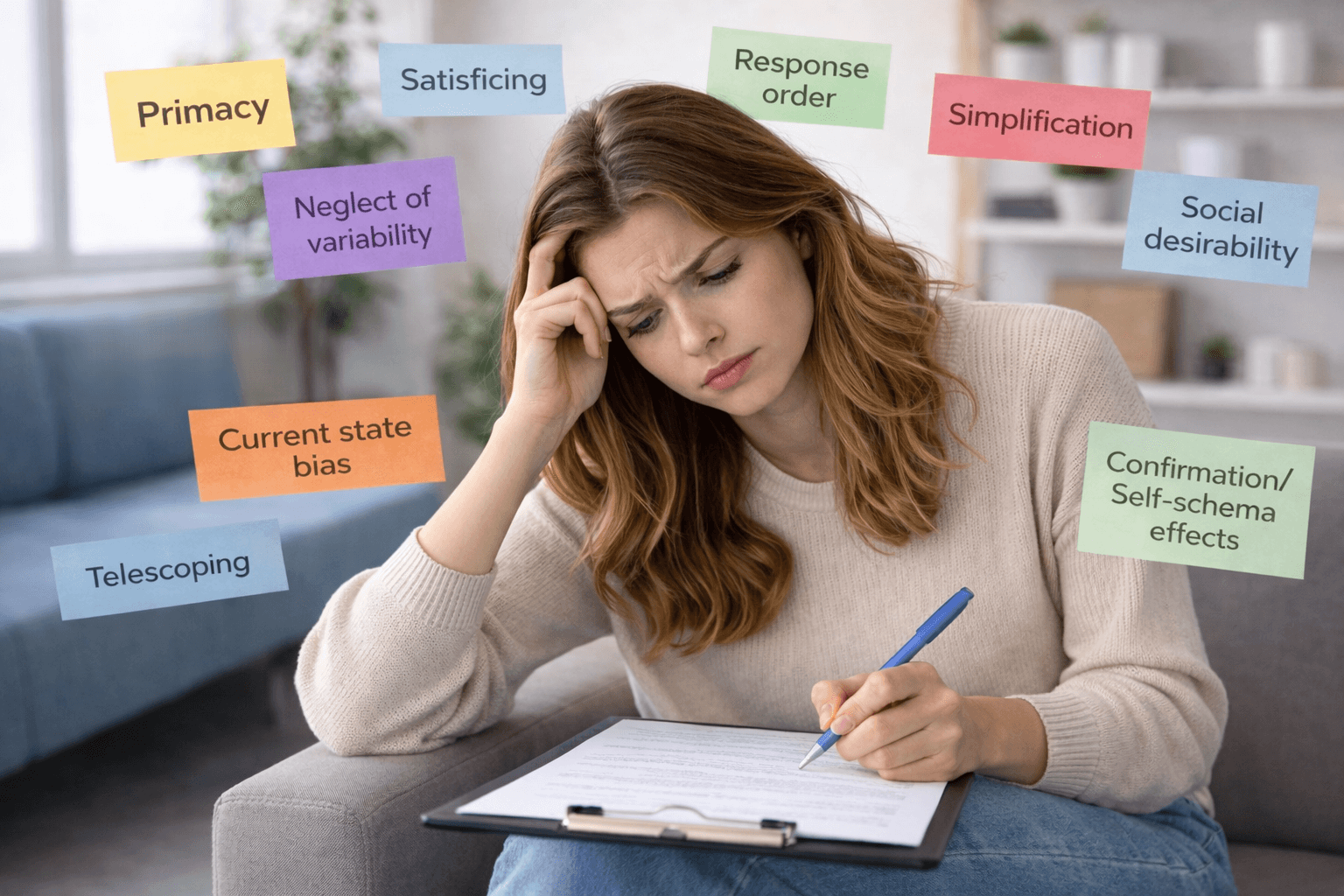

In this article, we examine nine of these secondary biases:

Primacy

Satisficing

Response order

Neglect of variability

Social desirability

Telescoping

Current state bias

Simplification

Confirmation/Self-schema effects.

Each introduces distortions that may seem subtle but can substantially shift the meaning of COA responses.

Primacy Bias

Just as recency bias highlights what happened most recently, primacy bias gives undue weight to what came first.

In a recall task, patients may remember the first week of a month-long window disproportionately, simple because those experiences were the earliest encoded. In a checklist item, the first few options may feel more “available” and thus more likely to be ticked.

Impact on COAs: Responses can be skewed upward or downward depending on whether early experiences in the recall period were unusually good or bad. Long lists of response options may inflate endorsement of items at the top.

Mitigation: Remind patients to consider the entire recall period, not just the start. Randomising the order of checklist options can also reduce primacy effects.

Satisficing and Cognitive Economy

Satisficing occurs when people give “good enough” answers instead of fully accurate ones to conserve effort. Working memory strain pushes people to take shortcuts.

In COAs, this often means defaulting to the midpoint of a scale (Sometimes) or ticking only one checklist option even if several apply. In longer questionnaires, patients may skim through without carefully considering each item.

Impact on COAs: Reduces sensitivity and discriminative power. Mid-scale clustering is common, masking true variability between patients or over time.

Mitigation: Keep items concise and avoid repetitive formative that induce fatigue. Highlighting that multiple options may apply can counteract underreporting in checklists.

Response Order Effects

The order in which options are presented influences choice. This is partly related to primacy and recency but also to simple scanning behaviour: patients are more likely to select options they see first.

In frequency scales, patients may gravitate towards extremes (Never or Always) if they appear at the ends. In checklists, top-list symptoms often receive higher endorsement.

Impact on COAs: Distorts endorsement patterns, particularly in items with many options. Data may reflect presentation order more than true relevance.

Mitigation: Randomise option order where possible or group options logically with clear headings rather than presenting a flat list.

Neglect of Frequency Variability

When aggregating experiences across time, patients simplify by treating variable patterns as stable.

For example, someone who had 20 good days and 10 bad days may report ‘sometimes’ for a symptom, even though the lived reality was a pronounced oscillations between extremes. This compression smooths out variability.

Impact on COAs: Loss of granularity and reduced sensitivity to change. Instruments may fail to detect cyclical conditions, such as migraines or mood disorders.

Mitigation: Ask about both average frequency and variability. Daily electronic capture can also highlight fluctuations masked by summary judgements.

Social Desirability and Self-Presentation Bias

Patients do not answer in a vacuum; they answer in a social and clinical context. Some adjust their responses to avoid stigma or to present themselves positively to clinicians.

This bias is especially strong for items about mental health, sexual functioning or treatment adherence. Patients may underreport depression, loneliness or missed medication.

Impact on COAs: Systematic underreporting of sensitive constructs. Not random noise but a directional bias that underestimates prevalence.

Mitigation: Use neutral, non-judgemental language; reassure patients about confidentiality; consider indirect questioning formats.

Telescoping Bias

Telescoping refers to misplacing events in time. Forward telescoping pulls older events into the recall window; backward telescoping pushes recent events out.

For example, a severe pain flare six weeks ago may be recalled as having happened in the “past month”, or a symptom two weeks ago may be forgotten as further back.

Impact on COAs: Distorts frequency estimates, especially with longer recall windows. Events are misclassified as inside or outside the timeframe.

Mitigation: Keep recall periods short (e.g. 1 week instead of 1 month). Provide anchoring cues (“since your last clinic visit” or “since the start of this treatment cycle.”).

Current State Bias

Patients’ current physical or emotional state influences recall and reporting. A patient answering a fatigue item while exhausted may recall more instances of fatigue and rate frequency higher. The same patient on a good day may minimise past fatigue.

Impact on COAs: State-dependent responding reduces reliability of data across instrument administrations. Changes in responses may reflect mood or context, not actual change in underlying symptoms.

Mitigation: Where possible, capture responses multiple times and average across states.

Simplification and Chunking Bias

To manage overload, people simplify. The “chunk” complex or variable experiences intro broad categories.

In COAs, this means collapsing nuanced symptom histories into categorical answers like ‘Always’ or ‘Never’, even if the true experience was variable.

Impact on COAs: Loss of sensitivity to moderate experiences or fluctuations. Makes longitudinal data less accurate.

Mitigation: Provide graded response options with concrete examples (“2-3 days a week”, “about half the time”).

Confirmation and Self-Schema Bias

Patients recall experiences that confirm their existing self-concept or narrative.

Someone who believes “my health is deteriorating” may selectively recall negative experiences, while a patient who believes “I am coping well” may underreport symptoms.

Impact on COAs: Skews responses towards consistency with self-schema, not lived reality.

Mitigation: Phrase items neutrally, include balanced items that probe both positive and negative aspects and triangulate with objective measures where possible.

Conclusion

These secondary biases remind us that COA responses are shaped not only by memory limits but also by the shortcuts that people use when under cognitive strain.

Primacy, response order and satisficing distort which options are chosen.

Telescoping and current state bias distort when experiences are placed in time.

Simplification and neglect of variability smooth out fluctuations into misleading stability.

Social desirability and confirmation bias inject social and self-presentational concerns into reporting.

The consequence is that COAs are not just measuring symptoms but also the patient’s ability to navigate memory constraints, presentation order and social context.

No questionnaire can eliminate bias entirely. But recognising these distortions allows us to design instruments that are less vulnerable: shorter recall periods, clearer anchors, randomised option order, neutral phrasing and opportunities to capture variability rather than averages.

Biases do not mean patient-reported outcomes are useless. They mean that patient reports are human reports, filtered through a mind that is bounded, emotional and adaptive. To honour the patient voice, we must design COAs that respect those realities.

Thank you for reading,

Mark Gibson, Leeds, United Kingdom

Nur Ferrante Morales, Ávila, Spain

September 2025

Originally written in

English